The fact that Bengaluru lacks an elected government significantly worsened the issue as the city experienced severe flooding over the previous week. The state government presently appoints bureaucrats to oversee the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike council because the tenure of the previous elected council ended in 2020.

One of the major cities in the globe is Bengaluru. More than eight million people live in the Greater Bengaluru region, which is comparable to the population of Switzerland. The fact that it lacks an elected government is, to put it simply, astonishing and highlights what is likely India’s worst governance weakness: a lacklustre, essentially nonexistent autonomous urban governance.

What’s visible in urban governance?

India has 675 million urban residents. This figure stands alone and exceeds the population of every nation outside of China. Additionally, India’s metropolitan areas produce about 60% of the nation’s GDP. According to consulting company Mckinsey, this will increase to 70% during the following ten years.

However, India has a shockingly poor administration when it comes to these densely populated, economically significant regions of the nation, as we saw in the case of Bengaluru.

Let’s start with the fundamentals: the urban governance in India is severely underfunded. India’s cities can only earn about 25% of their own money, with the remaining 75% coming from the Union and mostly the states.

Their state governments have restricted them administratively as well. When compared to other nations, the Constitution only lists a small number of duties that metropolitan governments are expected to carry out. State governments, and occasionally even the Union, have not allowed their municipalities to take on even those responsibilities, instead seizing tasks like constructing roads or providing water on their own.

For instance, in Bengaluru, the state, not the city, created the organisations responsible for managing water, sewerage, and land use—all traditional municipal duties. Even stranger, India’s federal government, which is in charge of 1.3 billion people, routinely meddles in the details of urban governance, such as sanitation (Swachh Bharat) or urban planning (Smart Cities Mission). The Mumbai Suburban Railway, the backbone of transportation for India’s financial centre, is operated by the Indian government rather than the city or the state, in what is arguably one of the starkest examples of centralization in the whole globe.

However, India’s urban administrations are severely political handicapped. Cities in India do not have access to the cabinet system of government, despite it being well-established at the state and union levels. Powerful mayors who can provide accountable governance in the same way a chief minister or prime minister can are uncommon in urban administrations. Even Mumbai, one of the most powerful cities in India, has a ceremonial mayor, and the government there is actually run by a bureaucrat chosen by the Maharashtra government. In contrast, the mayor of New York City, for example, is not only chosen by the city’s residents but also has influence over important institutions like the police.

Slipping behind the curve

Being the mayor of a significant city is a significant political position that frequently serves as a stepping stone to a national role all over the world. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan got his start as Istanbul’s mayor. Boris Johnson, the former British prime minister, served as mayor of London until 2016.

Ironically, China has much more powerful local administrations than India’s federal union while being a unitary state. Even stranger, India did formerly have strong mayors. For instance, Jawaharlal Nehru served as the mayor of Allahabad in the 1920s, as did Vallabhbhai Patel, his future deputy prime minister, in Ahmedabad. Subhas Chandra Bose was elected mayor of Kolkata in 1930. But a large part of this can be attributed to the fact that, up until 1937, Indians could only participate in democratic local government. Indians, who now controlled the central government following their independence, opted for centralization and weak local governments.

The role of local politics

It is important to remember that there have been initiatives to support local governance in India. West Bengal and Kerala both have political systems that aim to establish a strong third tier. In an effort to empower local governments financially and administratively by eluding state governments, the Union government introduced the 74th Amendment to the Constitution in 1992. In order to create a hybrid presidential-parliamentary government, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor submitted a private members bill in 2016 calling for a directly elected mayor as well as a cabinet named the “Mayor-in-Council” selected from elected councillors.

Notably, none of these actions has succeeded. By eroding municipal authority, states and, in some cases, the Union itself have avoided the goals of the 74th Amendment. In fact, even when reforms appear to be successful on paper, their real-world impact may be modest.

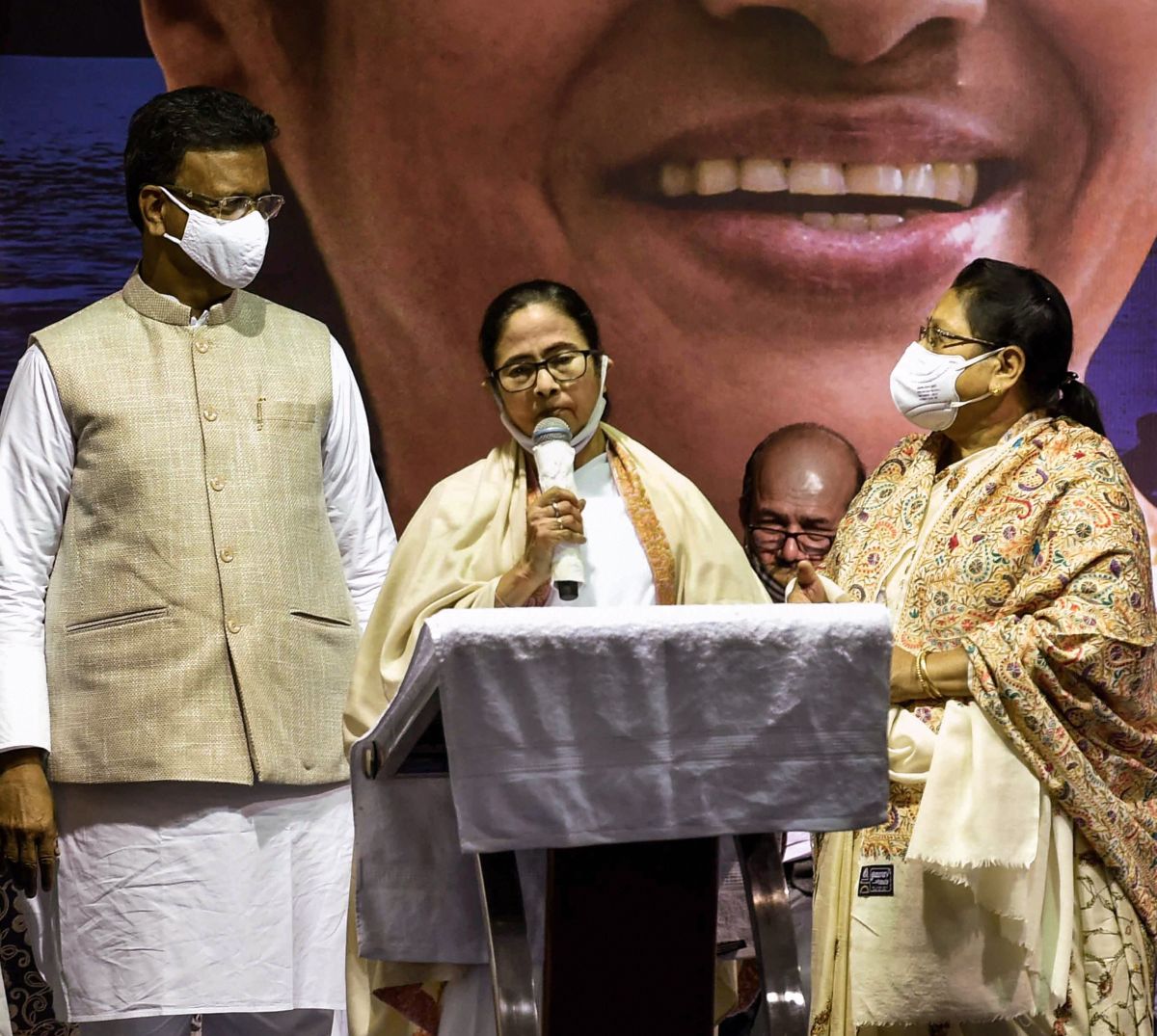

Using Kolkata as an example, the municipal corporation’s website claims that the city already has a “Mayor-in-Council, with all the qualities of the Cabinet form of government” in addition to a strong mayor who is chosen in the same manner as a chief minister or prime minister. However, Kolkata also emphasises the fact that, in the end, local politics prevail over the top-down organisational structure.

Although he may theoretically possess considerable authority over other local authorities, Kolkata’s mayor is politically beholden to the state’s chief minister and the ruling party. This holds true everywhere in the nation (in fact, given how centralised Indian politics are, it holds true even for the majority of state chief ministers who are members of national parties).

India’s local governance would remain in the same rut unless this political landscape changes.