Indian musical instruments in Army bands, new naval ensign, Raj Path renamed Kartavya Path. But one colonial legacy Modi hasn’t shown interest in eradicating is the Police Act of 1861. Forty-five annas worth of goods had vanished from the house in Katra Sheesh Mahal, nestled inside the lanes of Delhi’s Chandni Chowk: Kitchen utensils, women’s clothes, a hookah, and, mysteriously, a bowl of kulfi ice cream.

Late in 1861, Maeeduddin Yar Khan, son of Muhammad, walked into the Sabzi Mandi police station, one of three in Delhi, to report the crime. There is no way of telling what the police, over-burdened investigating gambling, prostitution, stolen mules and murders, made of the curious case of the kulfi thief. The crime was, however, recorded in the first-ever First Information Report.

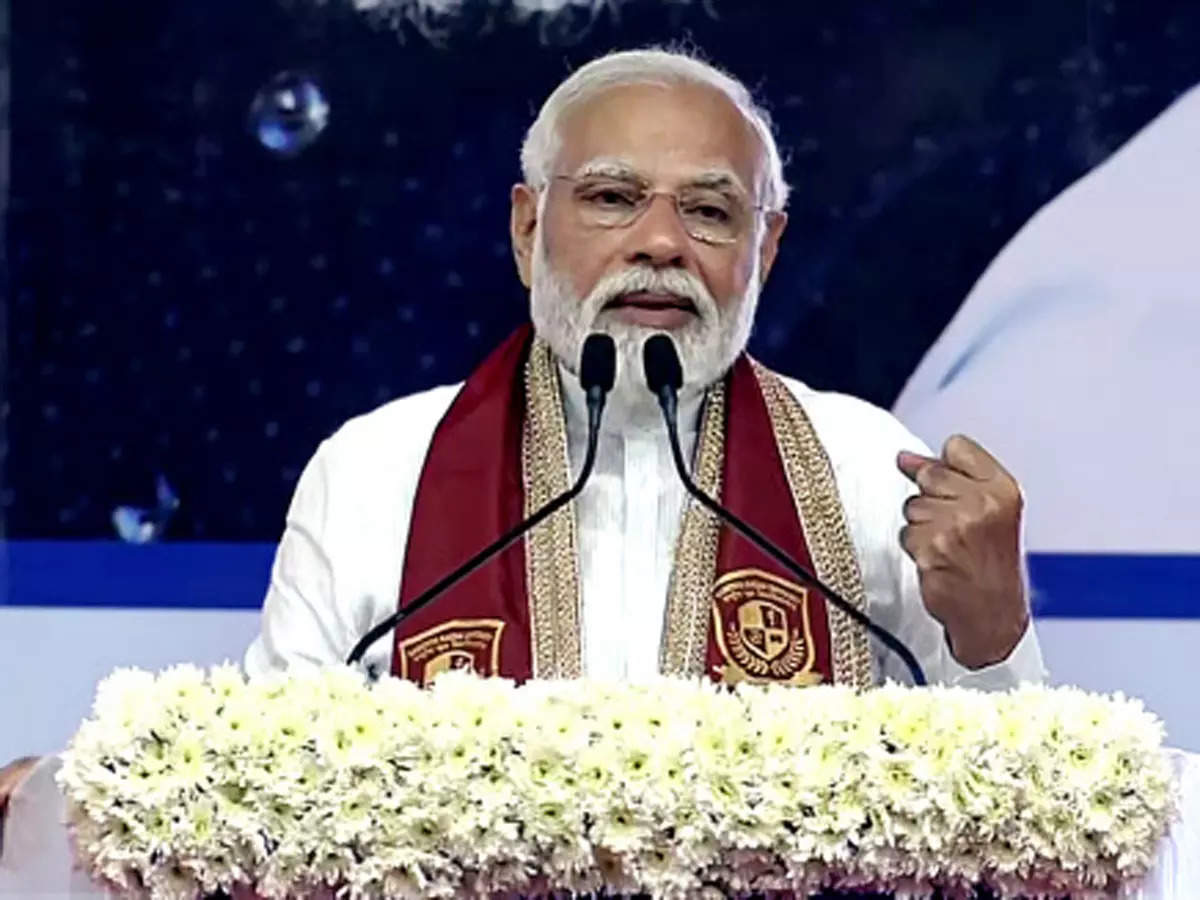

Ever since he took power, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been exhorting Indians to shed their colonial inheritance. Army bands have Indian musical instruments, there is a new naval ensign, and Raj Path has been renamed Kartavya Path. There is one colonial legacy, though, that Modi hasn’t shown interest in eradicating: The Police Act of 1861, which makes Indian police forces accountable to the political establishment but not the people.

Sixteen years ago this week, the Supreme Court laid out a blueprint for reforming the colonial-era governance of India’s police among other things, calling on state and central governments to set up independent bodies to regulate the appointment of its higher leadership. The reforms called for giving the police functional autonomy, demanding public accountability in return.

Last week, when four men rode down a highway in Bihar, shooting at random rampage, police have alleged, that was meant to spread fear of their gang—the costs of the failure to reform became evident. Local police completely failed to respond as the shooting proceeded, and that isn’t the only sign of a criminal justice system in disarray. Efforts to fast-track sexual assault trials are flailing, while new organised crime and terrorism threats are emerging.

Legislative models to replace the 1861 Act, emphasising police accountability, have long been in place. In the years since the Supreme Court judgment, 17 states have passed new Police Acts. But not one has implemented the independent system for appointments and tenure the Supreme Court mandated. In most states, political interference in appointments remains the norm—from the level of the Station House Officer to the Director-General. Appointments by the central government, too, remain clouded by opaque criteria and processes.