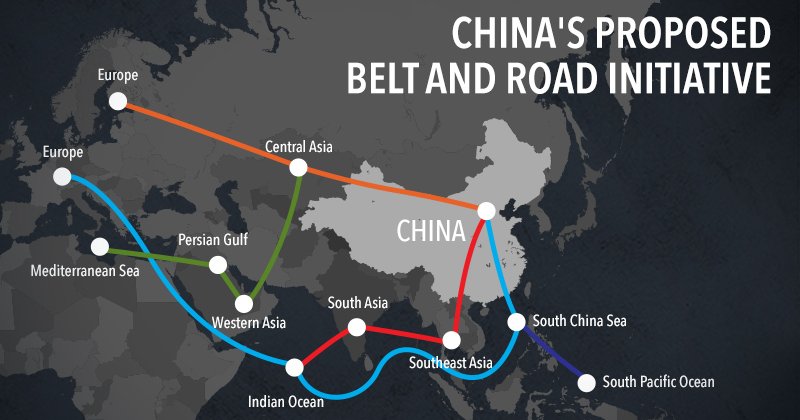

The China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ties China to the globe by creating a land-based “Silk Road Economic Belt” and a marine “21st Century Maritime Silk Road.” By March 2022, 147 countries had invested $28.4 billion in the BRI. Numerous BRI projects would go through ecologically sensitive areas and nations with inadequate environmental laws and governance, raising fears about severe environmental repercussions.

The BRI must prioritise green development. In 2007, the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) introduced “Ecological Civilization” (EC) as a response to environmental deterioration in China. In 2018, it was legally incorporated into the constitution and the country’s growth and development strategy.

Several policies have been released lately to encourage Chinese investors to include green development throughout the foreign investment process. The “Green Development Guidelines for Overseas Investment and Cooperation” issued on 15 July 2021 by the Ministries of Commerce and Ecology and Environment emphasise environmental impact assessments and other measures of enhancing host-country environmental protection (EIA). It requires following the host country’s regulations, funding renewable energy initiatives, and rehabilitating damaged ecosystems.

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced guidelines for environmental management in the energy, transportation, and mining sectors on 6 January 2022. It advocates avoiding protected regions and animal populations while establishing hydropower plants.

National Development Reform Commission, Commerce, Ecology and Environment, and Foreign Affairs Ministers released “Opinion on Jointly Promoting Green Belt and Road Development” on March 28, 2022. This ‘idea’ includes setting green BRI timelines and supporting low-carbon coal generation and other initiatives. It indicates China would stop building foreign coal-fired power facilities and “prudently” advance any current coal projects. This initiative aims to increase international project environmental risk avoidance by 2025. CBIRC called for “green funding” on June 1, 2022, to encourage low-carbon, sustainable development in China. This call includes lowering ESG exposure.

Some of these ideas are considered “soft law” since they cannot be enforced in court. Several Chinese state-owned banks’ strong participation in such projects raises worries about GHG emissions, especially from BRI coal projects. China participates in 240 BRI coal projects as of 2016. In the past five years, China’s support for coal plants has waned. President Xi Jinping assured the UN General Assembly in September 2021 that China won’t build new coal plants abroad.

China’s largest bank, ICBC, declared in 2021 that it would no longer support $3 billion of the 2,800 MW Sengwa coal project in northern Zimbabwe. CHEXIM will no longer fund coal projects in Bangladesh after 2022. BRI also noted that no coal projects had received finance or investment in 2022’s first half. 2 Gas (56%), solar/wind (18%), and oil (2%). (18 per cent).

CBRIC’s establishment of green finance guidelines shows that BRI’s environmental impact poses a financial risk. Myanmar’s Myitsone dam was cancelled due to resistance. After environmentalists sued the $1.2 billion, 1050 MW Lamu, Kenya coal plant, the courts stopped development in 2019.

The EIA implementation suggestions lack critical information on public involvement, a vital tool. Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007 recognise the importance of obtaining “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent” (FPIC) from affected communities before moving forward with large-scale infrastructure and extractive industries projects.

Several studies have highlighted the environmental dangers of BRI projects, especially linear projects like roads, trains, and pipelines, which pose the greatest hazards to already fragile ecosystems and critical biodiversity hotspots (KBAs). Due to the high concentration of mines near the proposed road and rail routes, one analysis determined that “construction and development along the route may increase mine size and number.” Up to 15% of unprotected KBAs are within 1 km of proposed railways, which might threaten biodiversity. Another study analysed biological invasion hazards in 123 BRI countries and identified 14 ‘hotspots’ with a high risk of terrestrial vertebrate invasion. 98 amphibians, 177 reptiles, 391 birds, and 150 mammals.

While many Chinese organisations attempt to solve environmental challenges, a study identifies a significant gap in conservation research capability: “China lacks a pipeline for teaching and developing conservation experts locally and internationally.”

Brundtland’s study defines sustainable development as meeting existing demands without jeopardising future generations’ ability to do so. Continuous reckless expansion endangers current and future generations. According to a recent UNEP report, the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and pollution demand synchronised solutions. Sir Partha Dasgupta says the loss of “natural capital” threatens the world economy. Poorly managed BRI projects may harm ecosystems and biodiversity. BRI project managers in China and the host nations must be cognizant of environmental risks.